Althusius and Covenantal Homogeneity

24 July 2024

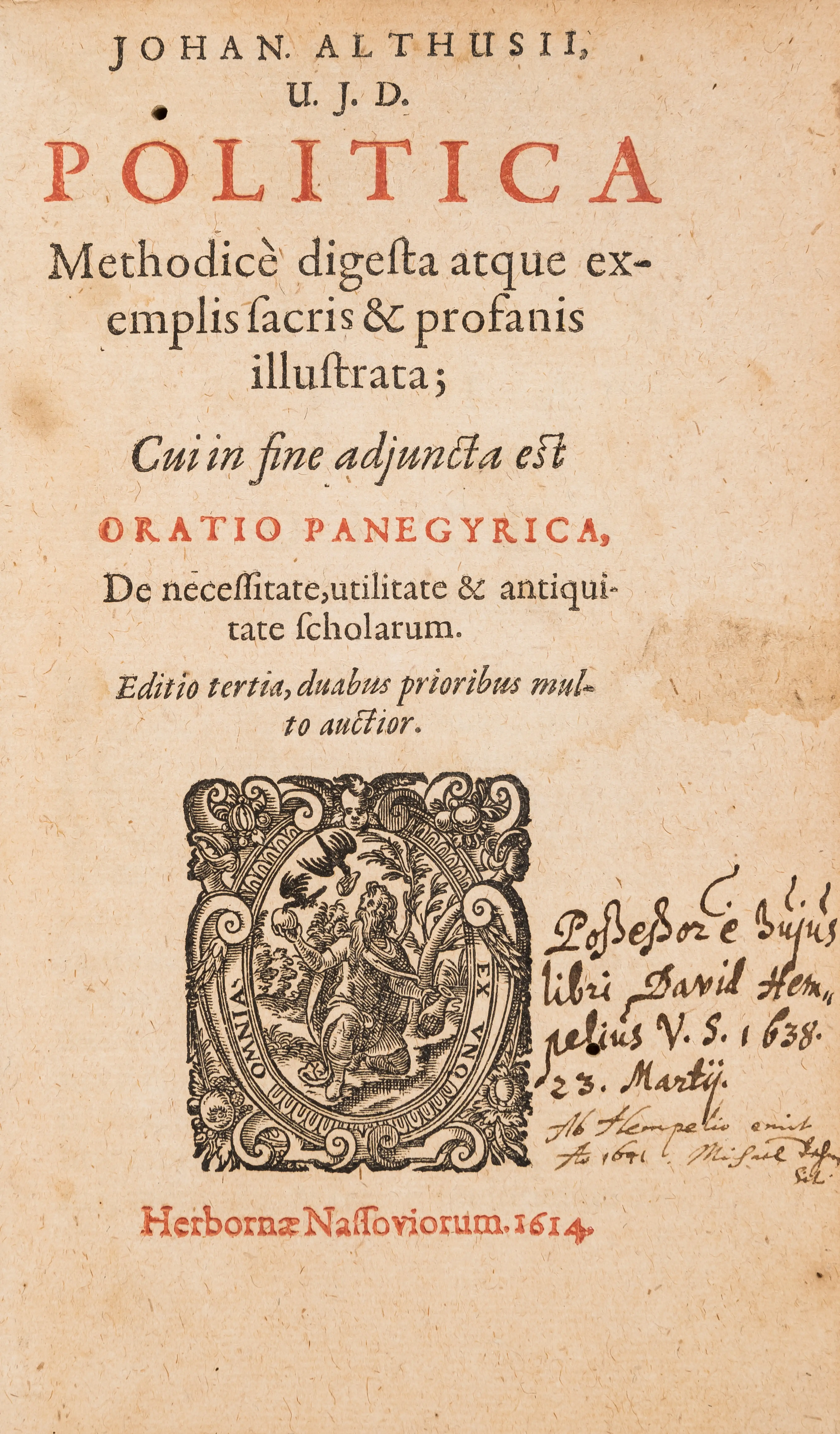

The influential Calvinist philosopher Johannes Althusius (1557—1638) is widely considered to be the first Federal (Covenantal) political theorist.1

He authored his magnum opus, entitled Politica, in the aftermath of the Treaty of Augsburg which was signed by the German princes in 1555. According to this treaty every German state, principality, free city or other political unit would have the right to determine whether its official religion would be Roman Catholicism or Protestantism. Within the German empire there would be room for both denominations, although each German tribe would maintain its own distinct religious identity. What is particularly noteworthy about this treaty, however, is that it did not view religious practice as a personal matter but as a public issue pertaining to the community as a whole. Althusius as Federal thinker explains the rationale behind this as follows:

The free [public] exercise of different religions is at odds with true faith and effectuates doubt in the minds of believers. The [public] presence of different faiths and many churches effectuates idolatry and apostasy. Moreover, diversity destroys unity.2

Althusius here does not hesitate to highlight the necessity of religious homogeniety in a Federal political order. I want to make the argument here that it is evident from his works that this principle of homogeneity has socio-ontological implications beyond the public religious domain to which it is applied here—a domain that would later aptly be described by the Dutch Reformed philosopher Herman Dooyweerd (1894—1977) as the "moral convictions and faith (pistis) of a people as publicly expressed in their national homeland."3

That this principle of homogeneity as advocated by Althusius not only applies to the ecclesiastical domain, but also has demographic implications for the political community as a whole is evident from his description of the nature and essence of the Federal socio-political order:

It cannot be denied that provinces are constituted from villages and cities, and commonwealths and realms from provinces. Therefore, just as the cause by its nature precedes the effect and is more perceptible, and just as the simple or primary precedes in order what has been composed or derived from it, so also villages, cities, and provinces precede realms and are prior to them. For this is the order and progression of nature, that the conjugal relationship, or the domestic association of man and wife, is called the beginning and foundation of human society. From it are then produced the associations of various blood relations and in-laws ... It is necessary, therefore, that the doctrine of the symbiotic life of families, kinship associations, collegia, cities, and provinces precede the doctrine of the realm or universal symbiotic association that arises from the former and is composed of them.4

For Althusius society as covenantally ordained and providentially ordered by God consists of social structures organically arising out of the most basic unit of human society, the family. Society emerges organically as familial or blood relations are extended to form tribes and nations. What is particularly noteworthy in this regard, is the fact that Althusius highlights the need for a Federal political order to reflect this organic and covenantal social structure. The province and the state must be a reflection of the tribe or people as the family writ large. Here we therefore find in the Politica a federalist foundation for the principle of homogeneity.

Federalism, as it has been historically understood within the framework of Calvinist political theory, necessitates socio-political and socio-religious homogeneity. The demographic implication of this theory is that liberal projects such as multiculturalism and mass immigration are essentially incompatible with the organic-covenantal nature of a Federalist social order, since it fundamentally undermines the familialist or tribalist nature of the covenant community. The Calvinist prime minister of Hungary, Viktor Orban, recently recognised this when emphasised the importance of "ethnic homogeneity" over against multiculturalism and mass immigration.5

A community, as extension of the family, can only flourish if it exhibits the same fundamental characteristics as the family, the most basic social unit. This includes a shared ancestry, shared religion, shared home or homeland, and shared socio-economic goals.

The Federal or covenantal answer to the demographic challenges facing Western nations today therefore entails starting with the reformation of family life as a covenantal life in accordance with the commandments of God's Law. Healthy, rooted families that live in accordance with God's will are unmissable to our political aim of establishing cultural spaces where our progeny can flourish and exercise self-determination. When these spaces organically emerge from what Althusius describes as the associations or collegia characteristic of a divinely ordained familialist social order, they will inevitably be marked by ethnic, cultural, and religious homogeneity.

1. Alain de Benoist, "The First Federalist: Johannes Althusius," Krisis 22 (1999): 2—34.

2. Althusius, Politica Methodice Digesta, Atque Exemplis Sacris et Profanis Illustrata (Groningen: Radeus, 1610), IX 45.

3. Herman Dooyeweerd, Wijsbegeerte der Wetsidee, Boek III: De individualiteits-structuren der tijdelijke werkelijkheid (Amsterdam: H.J. Paris, 1936), 368.

4. Althusius, Politica, XXXIX, 84.

5. DW, “Orban: ‘Ethnic homogeniety’ vital for economic success,” 3 March 2017: https://www.dw.com/en/hungarys-orban-ethnic-homogeneity-vital-for-economic-success/a-37755766.