John Calvin’s Geneva Catechism (1545) and Ethno-Christocracy

13 January 2025

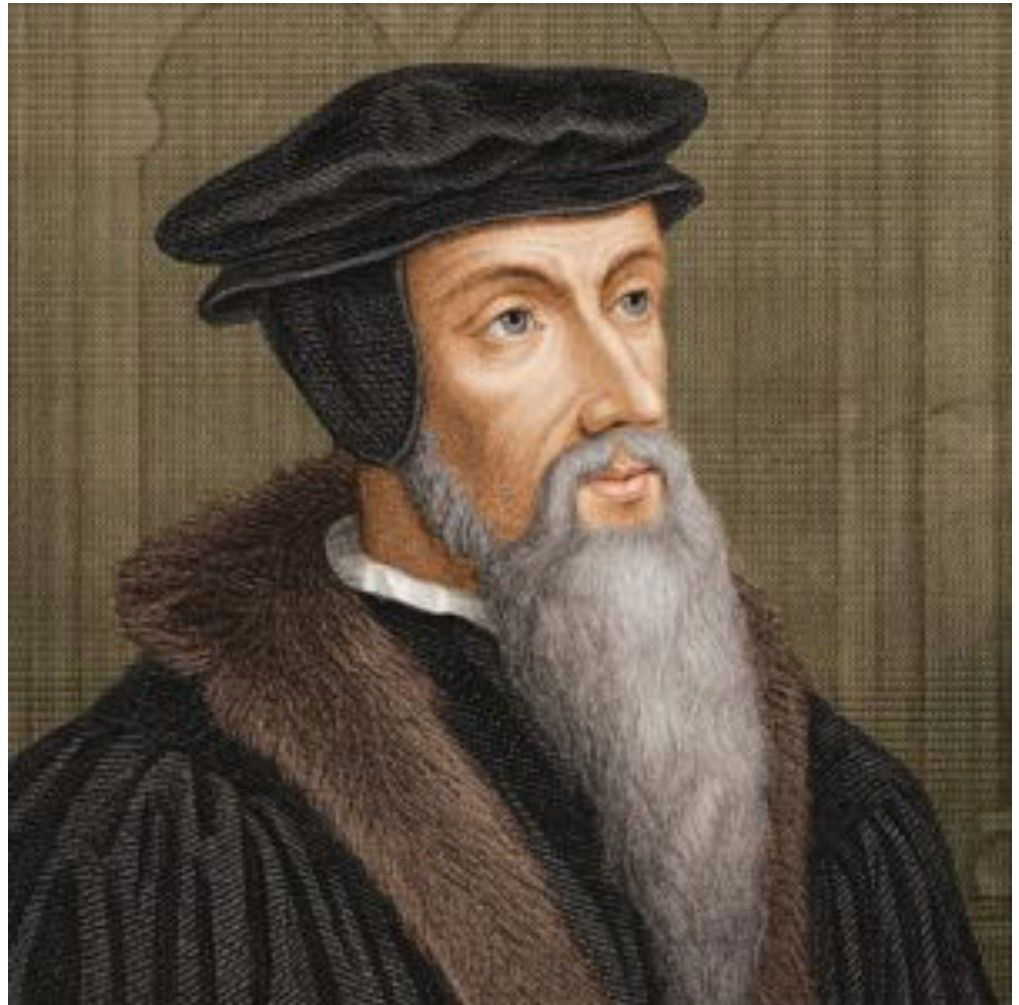

John Calvin authored the Geneva Catechism of 1545 during a critical and productive phase of his life, after his return to Geneva in 1541. This period marked Calvin's consolidation of authority and influence as a Reformer. Having initially been exiled from Geneva in 1538 due to conflicts with the city council over church governance, Calvin was invited back in 1541. By 1545, Calvin had begun to implement significant reforms in Geneva, aiming to create a model Christian community in the city of Geneva. He focused on establishing a structured church governance system, moral discipline, and doctrinal education. The Geneva Catechism was central to this effort, serving as a tool for education in the core tenets of the Reformed faith.

Calvin’s special concern for the people of Geneva as a covenantal city is evident in his emphasis on the salvation and well-being of their posterity, as expressed in the introduction of the Catechism. This Catechism was specifically written for the benefit of future generations of the Genevan people, with even the title of the Catechism reflecting its deep connection to a distinct people and place. This connection is, in fact, intrinsic to the very nature of confessional standards. As the Dutch Reformed theologian Abraham Kuyper once noted:

The Javanese are a different race than us; they live in a different region; they stand on a wholly different level of development; they are created differently in their inner life; they have a wholly different past behind them; and they have grown up with wholly different ideas. To expect of them that they should find the fitting expression of their faith in our Confession and in our Catechism is therefore absurd. The men are not all alike among whom the Church occurs. They differ according to origin, race, country, region, history, construction, mood and soul, and they do not always remain the same, but undergo various stages of development. Now the Gospel will not objectively remain outside their reach, but subjectively be appropriated by them, and the fruit thereof will come to confession and expression, the result may not be the same for all nations and times. The objective truth remains the same, but the matter in appropriation, application and confession must be different, as the color of the light varies according to the glass in which it is collected. He who has travelled and came into contact with Christians in different parts of the world of distinct races, countries and traditions cannot be blind for the sober fact of this reality. It is evident to him. He observes it everywhere.1

When treating the second commandment, where it is stated that God is a jealous God who visits the iniquity of the fathers on descendants, while showing intergenerational love to those who keep his commandments (Exodus 20:5—6), Calvin notes in the answer to question 154 of the Geneva Catechism that God “demonstrates his love for the righteous, by blessing their posterity, so he executes his vengeance against the wicked, by depriving their children of this blessing.” Here Calvin amplifies the intergenerational and familial affection and connection between ancestors and their descendants which together constitute a people or nation.

This same idea of national-covenantal intergenerational blessings and curses is again taken up by Calvin in his catechetical treatment of the fifth commandment. Here he treats the promise “that your days may be long in the land that the LORD your God is giving you” (Exodus 20:12). Question 193 of the Cathecism asks whether this promise does not only apply to the nation of Israel’s inheritance of the land of Canaan. The answer of the catechism reads as follows:

It does [speak of Canaan] in as far as regards the Israelites, but the term ought to have a wider and more extensive meaning to us. For seeing that the whole of the earth is the Lord’s, whatever be the region we inhabit He assigns it to us for a possession (Psalm 24:1, 85:5, 115:6).

Here we see that Calvin understands a land or a country to be the inheritance of a distinct people or nation. Just as God gave Canaan to the Israelites (an ethnic group) so he gives each ethnic group their own homeland as an inheritance. The collective "we" in this answer should therefore be understood as referring Christians in terms of their ethno-national identity. Calvin emphasises the same principle in his commentary on Acts 17:26, where he notes that

it was appointed before in God’s counsel how long he would have the state of every people to continue, and within what bounds he would have them contained. But and if he have appointed them a certain time and appointed the bounds of countries, undoubtedly he has also set in order the whole course of their life.

Here we see Calvin advocating for the principle of ethno-states. Two questions later, in the answer to 195 he also emphasizes that these ethno-states ought to be Christocratic in their civil order: “There is no authority, whether of parents, or princes, or rulers of any description, no power, no honour, but by the decree of God, because it so pleases him to order the world.” This demonstrates that both the division of civil realms along ethnic lines and the governance of those realms are to be conducted according to God’s order will, for it is Christ who rules the kingdom of God on earth, as Calvin’s Genevan catechism further underscores in question and answer 48, where it is asked:

In what sense do you understand Christ to be "our Lord?"

Inasmuch as he was appointed by the Father to have us under his power, to administer the kingdom of God in heaven and on earth, and to be the head of angels and good men.

1. Kuyper, A. 1904. Gemeene Gratie, derde deel: Het practische gedeelte (Amsterdam: Wormser), p. 233: “De Javanen zijn van een ander ras dan het onze, ze leven in andere landstreek, ze staan op geheel anderen trap van ontwikkeling, ze zijn in hun gemoedsleven geheel anders aangelegd, ze hebben een geheel ander verleden achter zich, ze zijn opgegroeid in gansch andere denkbeelden. Van hen te verwachten, dat ze in ónze Confessie en in ónzen Catechismus de passende uitdrukking van hun geloof zullen vinden, is daarom ongerijmd, en steeds luider wordt de vraag naar een uiting van kerkelijk leven die voor de Javanen geeft, wat onze Kerk ons biedt.

Dit nu is niet iets bijzonders voor de Javanen, maar vloeit voort uit een algemeenen regel. De menschen zijn niet eender onder wie de kerk optreedt. Ze verschillen naar herkomst, ras, land, streek, verleden, aanleg, gemoedsstemming en zielsbestaan, en ook blijven ze niet altoos dezelfde, maar doorloopen verschillende trappen van ontwikkeling. Zal nu het Evangelie niet voorwerpelijk buiten hen blijven liggen, maar onderwerpelijk door hen worden toegeëigend en als vrucht hiervan tot belijdenis en uiting komen, dan kan het resultaat niet voor alle volken en tijden gelijk zijn. De voorwerpelijke waarheid blijft wel één, maar de onderwerpelijke toeeigening, toepassing en belijdenis moet verschillen, evenals de kleur van het licht verschilt naar gelang van het glas waarin het wordt opgevangen. Wie gereisd heeft en in meerdere werelddeelen met Christenen van onderscheiden rassen, landen en traditiën in aanraking kwam, kan dan ook voor het nuchtere feit, dat het zoo is, het oog niet sluiten. Hij ziet het voor oogen. Hij neemt het altoos en overal waar.”