Peter Harrison on the Modernist Natural/Supernatural Dichotomy

27 February 2025

By Dr Adi Schlebusch

In a recent essay by professor Peter Harrison of the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Queensland in Australia, he does a spectacular job of debunking the commonly held historical narrative that science "liberated itself" from and "triumphed over" religion to produce the scientific breakthroughs associated with the Newtonian revolution.

In the essay, entitled, The Birth of Naturalism: Investigating the Roots of the natural/supernatural dichotomy, Harrison presents a compelling argument that the historical study of the natural world itself was shaped by theological foundations, particularly through the concept of the laws of nature, which early modern scientists understood as expressions of divine will. The naturalist perspective of late modernity which became prevalent in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and which treats the laws of nature as brute facts intrinsic to the universe, only emerged after a deliberate reinterpretation of history that downplayed or erased these theological origins.

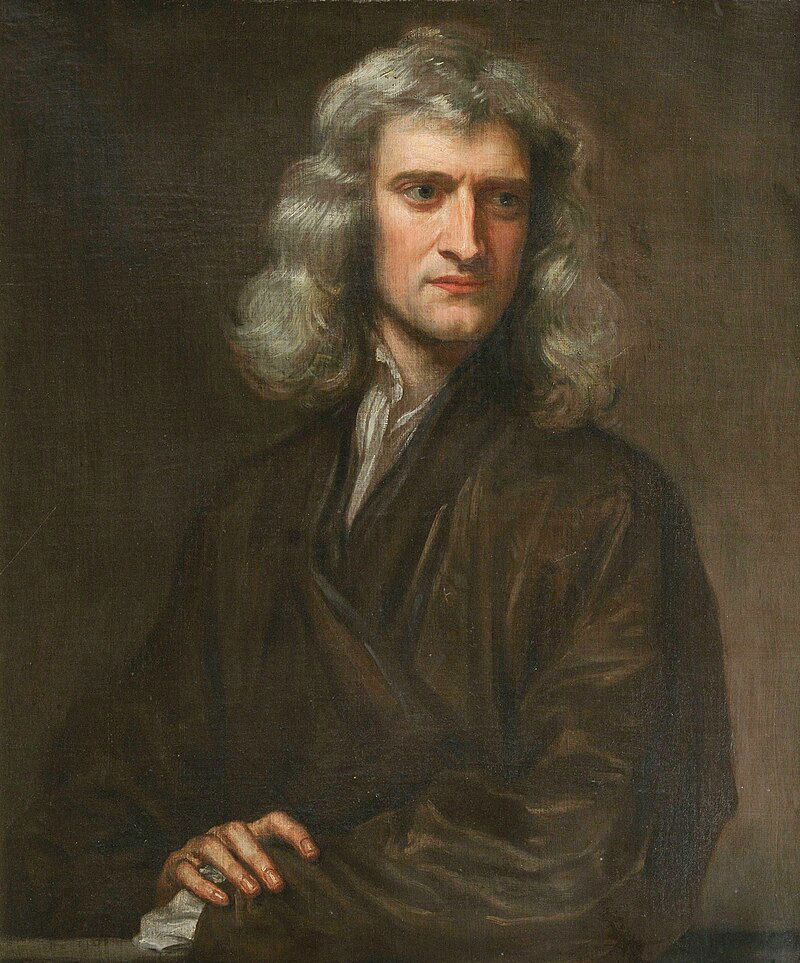

Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton, and other key figures in the seventeenth-century scientific revolution held that the laws governing the universe were rooted in divine volition. Newtonian thinkers like Richard Bentley and Samuel Clarke went so far as to argue that nature itself was merely an expression of God's will in action. In this framework, there was no real distinction between natural and supernatural; what we now call "natural laws" were simply understood as the predictable ways in which God sustained and governed the world.

However, during the 19th century, figures such as Thomas Huxley, a key proponent of scientific naturalism, sought to redefine these ideas by stripping them of their theological underpinnings. The notion of natural laws, originally seen as evidence of divine order, was repurposed as proof of a self-sufficient, purely material universe. This marked a dramatic shift: the very concept that had once supported religious belief was now used to justify its rejection. This transformation was not a neutral or purely scientific development but a deliberate ideological shift. Nineteenth-century thinkers obscured the extent to which early scientists relied on theological assumptions by producing distorted Enlightenment-era historiographical narratives that positions ancient Greece as the sole birthplace of philosophy and science while portraying the Middle Ages as a period of intellectual stagnation caused by Christianity.

David Hume, for example, wrongly portrayed early Greek philosophers as naturalists who rejected supernatural explanations. Yet, as Aristotle's account of Thales of Miletus suggests, these early thinkers did not separate nature from divinity but saw the world as governed by a pervasive divine force. In fact, Harrison points out just how radically distorted this view of ancient philosophy really is:

It is certainly true that, when early Christian thinkers came to assess the scientific contributions of their Greek predecessors, they were somewhat ambivalent. For at least some of them, however, this was not owing to an animus against naturalistic science. On the contrary, it was because they encountered too many gods and divine powers at work in the natural world. The prevailing science was deemed to be too promiscuously supernaturalistic. Christian thinkers typically denied the divinity of the heavenly bodies and their capacity to be self-movers, for example. The adoption of monotheism could thus promote an ethos of naturalisation and disenchantment.

It was partly for this reason that the early Christians were considered to be atheists by their pagan contemporaries. They believed in an insufficient number of deities.

While Harrison's essay is generally very enlightening and refreshing, its weakest element is undoubtedly his idea that this historical revisionism of the eighteenth- and nineteenth centuries was deeply intertwined with what he describes as "Eurocentric" and "racist" ideologies, by which figures like Hume and Meiners dismissed the intellectual contributions of non-European civilizations as incapable of abstract reasoning and scientific thought. While we don't deny that many post-Enlightenment thinkers may have disregarded some historic non-European contributions to science and may have been Eurocentric in their thought, this cannot in any way be considered the root cause for their rejection of the role of Jerusalem in shaping Western civilization along with Athens. In fact, if anything the Enlightenment produced oikophobia rather than nationalism, and therefore the Eurocentricism of figures such as Hume can be considered something they actually inherited from their traditional Christian culture. After all, at the time Europe was the only continent in the world which had been historically shaped by Christianity. Finally, these liberal thinkers, by Harrison's own admission, also characteristically denied many medieval European contributions to science.

Nonetheless, Harrison's analysis does a brilliant job of challenging the false assumption that scientific progress arouse from some kind of naturalistic/supernaturalistic dichotomy. As the pioneers of scientific thought operated within a theological framework, the supposed conflict between science and religion suggested by modern narratives did not exist with the Newtonian revolution. Moreover, the very distinction between natural and supernatural—so central to modern naturalism—is itself a recent and artificial construct rather than a historic feature of human thought.

The full essay can be read here.