The Theocratic Mandate of Article 36 of the Belgic Confession

May 27th 2024

By Dr Adi Schlebusch

The debate surrounding what eventually came to be considered the highly controversial statement in article 36 of the Belgic Confession of Faith, namely that it is the government's task to not only protect true religion, but also to “prevent all idolatry and false worship,” is, much like chapter 23 of the Westminster Confession (on the civil magistrate), one that has divided the Reformed world for a very long time.

The Belgic Confession, one of the three primary confessional writings in the Dutch Calvinist tradition, serves as a distinguished systematic expression of Christian doctrine. Drafted by one of John Calvin’s contemporaries, Guido de Brès (1522—1567), the confession holds significant historical and theological importance. Notably, De Brès, who held Calvin in high esteem, sent him a copy of this confession, with Calvin noting that he is in full agreement with the contents of the entire confession with the exception of the authorship of the Book of Hebrews being attributed to Paul in article 4.1 The confession was originally written in French, as De Brès hailed from Wallonia, in the southern part of Belgium, which at the time formed part of the Low Countries or the Netherlands. Officially recognized as confessional standard by the Dutch Synod of Dort in 1618/19, this sixteenth-century confession originated against the backdrop of Spanish Roman Catholic domination, with the country being officially known as the Spanish Netherlands at the time.

The Roman Catholic government of the day refused to tolerate the Reformed Religion. This context is crucial, as article 36 of the Belgic Confession advocated the suppression of idolatry even at a time when Reformed believers were denied the freedom to practice their religion, precisely because the Spanish government considered it to be idolatry. What therefore makes article 36 of the Belgic Confession of Faith particularly striking is the fact that, even despite being authored at a time when the Reformed religion was under pressure from the civil government, it does not call for religious freedom or pluralism but rather for a Calvinist theocracy. This sentiment was prevalent among Reformed believers of the time. For instance, a few years after De Brès drafted this confession, the Reformed churches in the Spanish Netherlands appealed to the Protestant queen of England and Ireland, Queen Elizabeth I, requesting intervention for the Reformed believers under Spanish Roman Catholic rule. In their letter they emphasized that this "free exercise of ... the pure religion," i.e., the Reformed religion, must only be granted "with the exclusion of all other false practices in any way."2

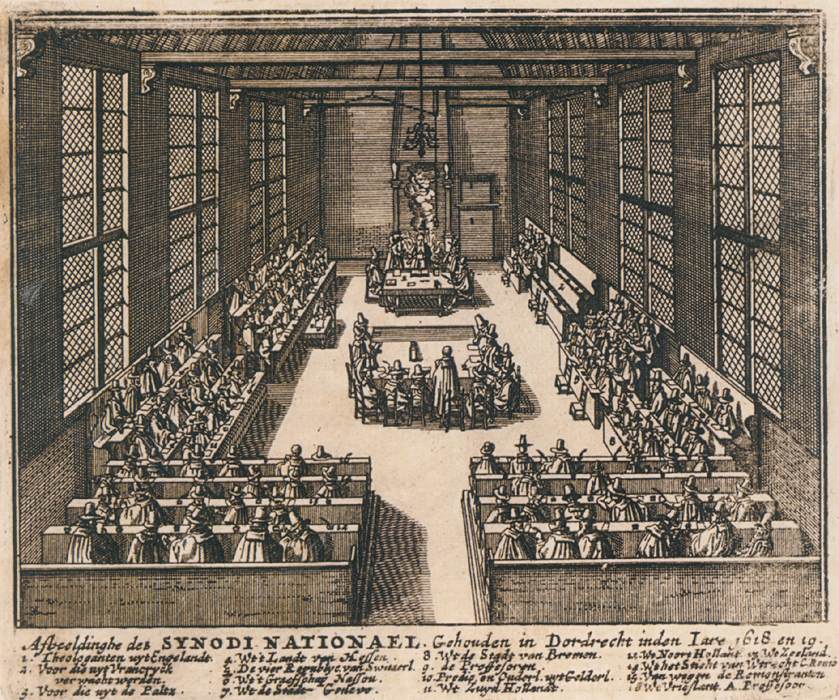

When the Synod of Dort officially adopted this confession a few decades later, they also officially decided during their 177th sitting to write an official request to the government to enact stricter laws against “the exercise of papal idolatry and superstition as well as the blasphemies of the Jews.”3 The Synod of Dort therefore did not advocate for religious freedom or pluralism. While they endorsed freedom of conscience, it is abundantly clear that they did not support religious freedom in the public domain.

Almost 300 years later, at the end of the 19th century, Dutch society had largely apostatized from Christianity. Although most people in the Netherlands by the end of the 19th century were probably still churchgoers, political and social life had been radically secularized since the second half of the 19th century due to lamentable philosophic influences of the Enlightenment. Consequently, article 36's claim that the government’s duties include “preventing and eradicating all idolatry and false religion, destroying the kingdom of the Antichrist and promoting the kingdom of Jesus Christ," was increasingly being viewed with suspicion.

Within this context of Dutch society's historical secularization, or better put, its de-confessionalization, the Neo-Calvinists Abraham Kuyper and Herman Bavinck proceeded to articulate objections to the idea that the government’s duties includes suppressing idolatry and false worship. Notably, they did not argue for this position on mere pragmatic grounds, though, but treated it as a matter of principle. They did not claim that this article was no longer relevant in their time, but admitted to holding a principled disagreement with it. For the Neo-Calvinists, religious freedom was a Christian principle. This stance represented a significant departure from De Brès, Calvin, and the Synod of Dort.

Yet despite their liberal stance, Kuyper and Bavinck still strongly opposed any idea that public life or the political sphere falls outside Christ's Lordship and His revealed will in the Bible. There is no mention in the works of either Bavinck or Kuyper of any part of life that is not under Christ's Lordship and the authority of His Word. Bavinck, for example, goes so far as to say that "from the Old Testament law, the eternal principles are derived, which alone can guarantee the existence and welfare of family, society, and state," maintaining that it is an abomination "to grant error equal rights with the truth."4

With this in mind, how did Kuyper and Bavinck justify their resistance to a Christian state where Christianity is institutionally promoted and the public practice of other religions is prohibited? Of course, Article 36, even in its original form, does not condemn freedom of conscience. It does not imply that the state should monitor personal religious practices, but rather addresses public religious practice, meaning zero tolerance for mosques, synagogues, humanistic or atheistic clubs, or similar organizations. It does not affect personal conscience nor compel belief in Jesus Christ by force. Kuyper and Bavinck grasped this and yet still opposed its theocratic mandate.

In order to do this the Neo-Calvinists created a new category completely foreign to traditional Calvinism. Whereas the latter makes a sharp distinction between the sinful, depraved natural life and the life from grace through the Holy Spirit, Kuyper adds a third category, life from common grace, asserting that common grace reveals certain truths to all people, thereby forming an important point of agreement between believers and unbelievers, whereas Calvin maintained that “all human faculties are corrupt, so that of themselves they can bear only evil fruit. In addition this grace is not given to all without distinction or generally, but only to those whom God wills; the rest, to whom it is not given, remain evil and have no ability to attain to the good.”5

Neo-Calvinists, however, argue that natural revelation should take precedence in public and political life, with Kuyper claiming that the state is "directly built only on natural knowledge of God; and therefore, the government is active in the sphere of natural knowledge of God, but passively serves God in the sphere of revealed knowledge."6 Thus, the government should actively obey natural revelation while it passively obeys the Bible. Bavinck supports this, stating that the Holy Spirit's guidance is needed to distinguish between true and false religion, which the government cannot do.7

This of course raises the question of whether the government can discern any truth at all, given that Christ's resurrection and reign are no less true or objectively revealed than any social or political truths are. Bavinck unfortunately leaves this question unanswered. Furthermore, Kuyper and Bavinck's idea that natural revelation is "clearer" than Scriptural revelation contradicts the Belgic Confession of Faith itself, which states in Article 2 that Scriptural revelation is in fact clearer than natural revelation. Nevertheless, under Bavinck and Kuyper's leadership, Article 36 was indeed amended in 1905 during the Synod of the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands—a regrettable moment in Reformed church history.

It cannot be denied that Kuyper and Bavinck’s deviation from the view of the human moral state as depraved outside of Christ and enlightened in Christ, represents a significant departure from orthodox historical Calvinism and led to an erroneous rejection of the theocratic mandate of article 36 of the Belgic Confession. Because of their errors they also overlooked the fact that every state necessarily adopts a particular religion, and that the secularization of the West in the 19th and 20th centuries was not so much a rejection of religion as such, but the replacement of Christianity with Humanism as guiding principle for public life. In reality, there can never be genuine neutrality, for as Jesus said in Luke 11:23: "He who is not with Me is against Me."

1. Stewart, A. Lecture on the Belgic Confession. URL: cprc.co.uk/belgicintro.mp3.

2. Bor, P.C. 1681. Oorspronck, begin, en vervolgh der Nederlandsche oorlogen, beroerten en borgerlyke oneenigheden. Historie der Nederlandtsche oorlogen onpartydiglyk beschreven, deel drie. Amsterdam: Boom, p. 262, 265.

3. Glasius, B. 1860. Geschiedenis der Nationale Synode, in 1618 en 1619 gehouden te Dordtrecht, in hare voorgesciedenis, handelingen en gevolgen. Leiden: Engels, p. 948.

4. Bavinck, H. 1892. Welke algemeene beginselen beheerschen, volgens de H. Schrift, de oplossing der sociale quaestie, en welke vingerwijzing voor de oplossing ligt in de concrete toepassing, welke deze beginselen voor Israel in Mozaisch recht gevonden hebben? Proces-verbaal van het Sociaal Congres, gehouden te Amsterdam den 9, 10, 11, 12 November 1891. Amsterdam: Höveker & Wormser, p. 5.

5. Calvin, J. 1543. The Bondage and Liberation of the Will, 325.

6. Kuyper, A. 1879. “Ons program”. Amsterdam: Kruyt, p.189.

7. Bavinck, H. 1904. Christelijke wetenschap. Kampen: Kok, p. 94.