The Heresy of Propositional Covenantalism

5 December 2024

Introduction

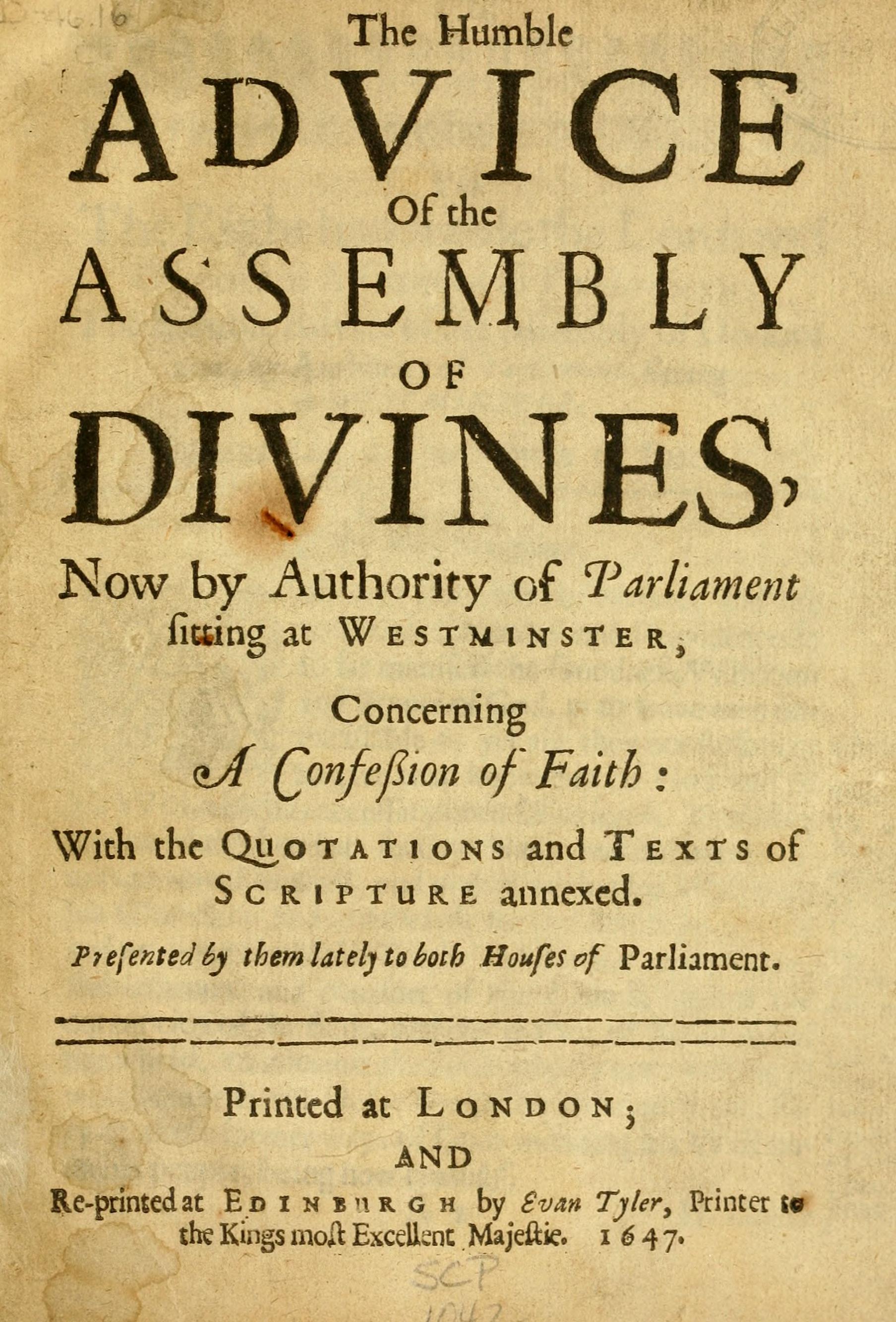

A number of leading figures in the Reformed world are quietly turning the historic Christian doctrine of the covenant on its head. Historic covenant theology has always understood the covenant as a divinely initiated pact whereby God binds creation and humanity to Himself. Covenant therefore presupposes the Creator/creature distinction as this distinction manifests in the transcendence of God on the one hand and then on the other hand creation as called into existence by a sovereign God who sustains it by his providence. This includes not only creation as an abstract concept, but “all things therein whether visible or invisible” (Westminster Confession 4.1). This means that the very aspects or dimensions of creation and the distinctions accompanying these have been created by God for his sovereign purposes in Christ. As such, the covenant of grace manifests not as a detached spiritual abstraction but as the renewal of life within the created order. The Westminster Confession (7.6) also speaks of the covenant as being dispensed and administered “to all nations, both Jews and Gentiles.” Propositional covenantalism fundamentally deviates from this historic view of the administration of the covenant to the God-given creational realities of the family, clan, city, tribe and nation. By reducing covenant theology to an abstract system, it denies the significance of God-given covenantal structures as outlined in the Westminster Confession of Faith.

This heterodox view, articulated in the Antioch Declaration as the affirmation "that the ultimate bond or good for temporal human life is not grounded in absolute loyalty to blood and soil, family or nation, but in the totalizing bond of the Kingdom of God through the Covenant of Grace," pits grace against nature by virtue of its denial of the reality that grace is covenantally maintained through the natural relations and collective social structures embedded in human nature and the created order. In contrast it proposes an unbiblical individualist view of covenantal administration, thereby undermining the Reformed confessions.

Creation and Redemption

Biblical theology affirms that God's covenantal operations are intrinsically tied to the structures of human life. From the beginning, God’s covenants have included not just individuals but their descendants as families and nations.

In Scripture, the family is central to the administration of the covenant. God’s covenant with Abraham expressly includes his offspring (Genesis 17:7), and the promises of salvation are repeatedly described as extending “to you and your children” (Acts 2:39). This familial continuity underscores the very centrality of the family in the covenant in terms of raising the next generation of faithful in the fear and admonition of the Lord.

This stands in stark contrast to propositional covenantalism, which treats covenant membership as an abstract, individualistic reality detached from the organic, intergenerational nature of the family unit held together by blood relationships. In this regard, propostional covenantalism has essentially adopted a liberal anthropology and projected it upon the Biblical covenant.

Nations also play a key role in the redemptive and providential unfolding of God’s covenantal purposes. In Deuteronomy, the nation of Israel is presented as a covenant community chosen by God to manifest His redemptive purposes in history. The Reformers did not see this as limited to Israel but as extending to all nations under the New Covenant. In other words, just as God ordained Israel to be a nation unto Himself, so too does He call all nations to submit to His rule, that they might serve as instruments of His Kingdom.

Importantly, Covenant theology does not conflate national identity with salvation but recognizes that God works through the created and ordained social structures from which humanity is constituted in order to accomplish His redemptive plan. Propositional covenantalism, however, completely disregards God’s creational and redemptive order, and portrays God’s Kingdom as a purely spiritual abstraction with no bearing on the natural world.

The Errors of Propositional Covenantalism

Propositional covenantalism’s departure from historic covenant theology manifests in several key errors:

1. A Denial of organic intergenerational covenantal continuity

By viewing the object of the administration of the Covenant of Grace not primarily as families and nations, but as atomized individuals, propositional covenantalism rejects the organic continuity of God’s covenantal interactions with peoples in their generations through covenantal lineage. This view ignores the relational depth of God’s covenant, which unfolds through natural social units like families, cities, and nations, and instead presents a sterile, individualistic interpretation, which falsely dichotomizes God's work as Creator and God's work as Redeemer.

2. A Rejection of Grace’s Transformative Role in Nature

Bavinck highlights that grace does not destroy nature but redeems it. Propositional covenantalism undermines this biblical truth by treating grace as something detached from the natural order. In doing so, it promotes a dualistic view of reality that is fundamentally at odds with the holistic perspective of historic covenant theology. During this Christmas season especially, we highlight the corporeal and earthly elements of God’s redemptive work in Christ who was specifically and purposefully incarnated not as an abstract individual, but as a member of the family of David, the tribe of Judah, and the nation of Israel.

3. A Denial of the Kingdom’s Earthly Manifestation

The Kingdom of God is not merely a spiritual reality but is a reality that transforms and incorporates all aspects of life on earth, including not only individuals, but families, cities, tribes, and nations. Propositional covenantalism abstracts the Kingdom into an wholly otherworldly concept, ignoring the God-ordained covenantal framework through which Christ reigns and triumph’s in history.

Conclusion

To counter the errors of propositional covenantalism, the church must recover the biblical and Reformational understanding of the Covenant of Grace. This entails recognizing God’s covenant as being not merely an abstract agreement, but a very real relational bond established by God. This bond involves real people, families, cities, and nations, unfolding within the created order. As such, God’s redemptive purposes are not isolated from the structures of creation. Families and nations are covenantal contexts through which God works to bring His Kingdom on earth as it is in heaven (Matthew 6:10). Adveniat regnum tuum!

Grace operates within the framework of the natural order, redeeming it for God’s glory. Covenant theology must reflect this, meaning that we must oppose the gnostic tendencies of propositional covenantalism, which ultimately severs the organic connection between God’s redemptive purposes and the structures of human life.

As the church confronts this error, we must reaffirm the truths articulated by the Reformed Confessions: that grace restores nature, that covenants unfold through families and nations, and that God’s Kingdom encompasses all of life and every aspect of created reality. Only by returning to this robust, biblical understanding can the church faithfully proclaim, to every nation, the covenantal love of God and the glory of His redemptive plan.